Kings of Bakubung

The past Kings and the present King

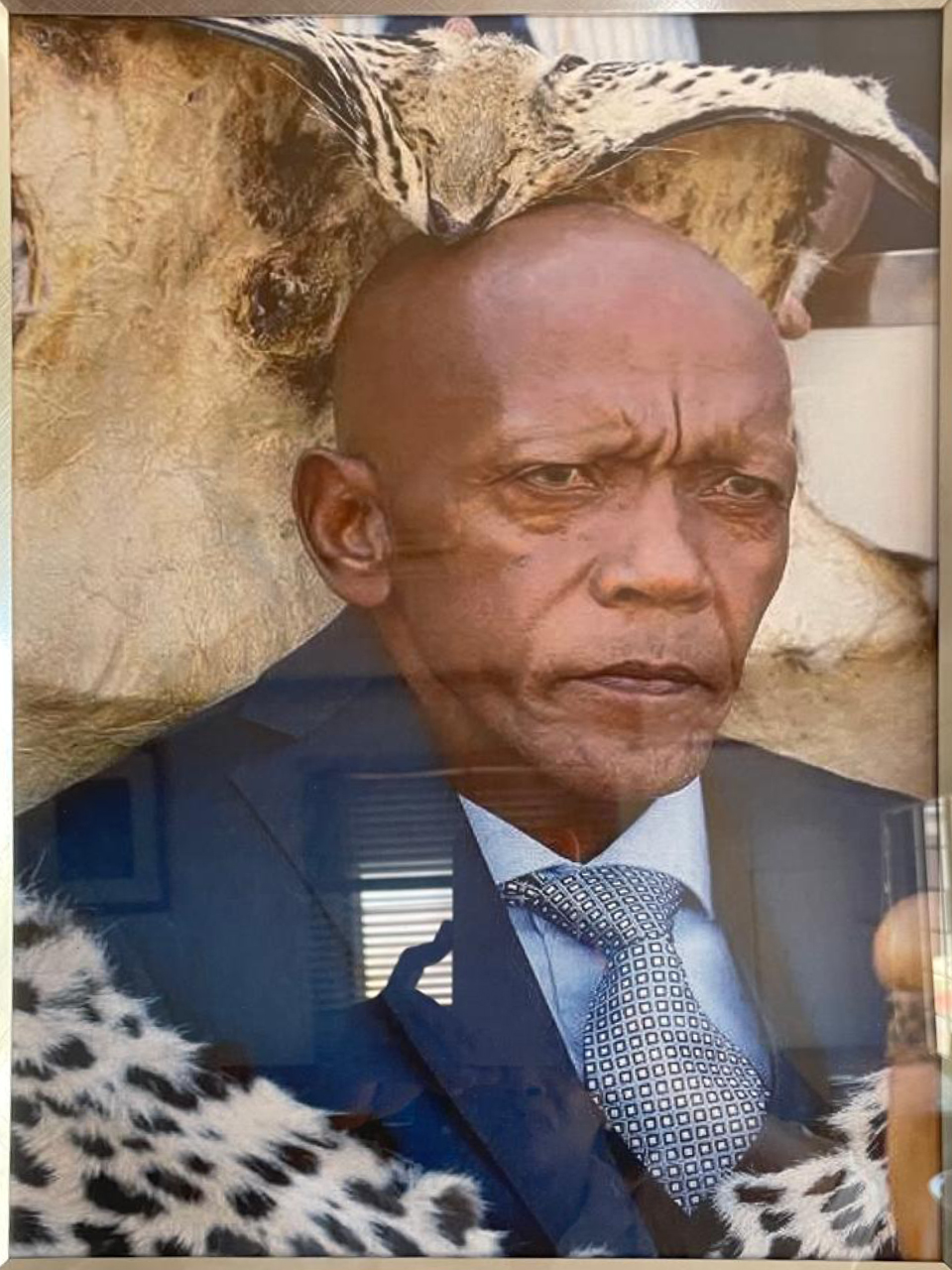

Kgosi Solomon Mphuphuthe Monnakgotla

(2016 - Present)

Kgosi David Gabonewe Monnakgotla

(1977 - 2009)

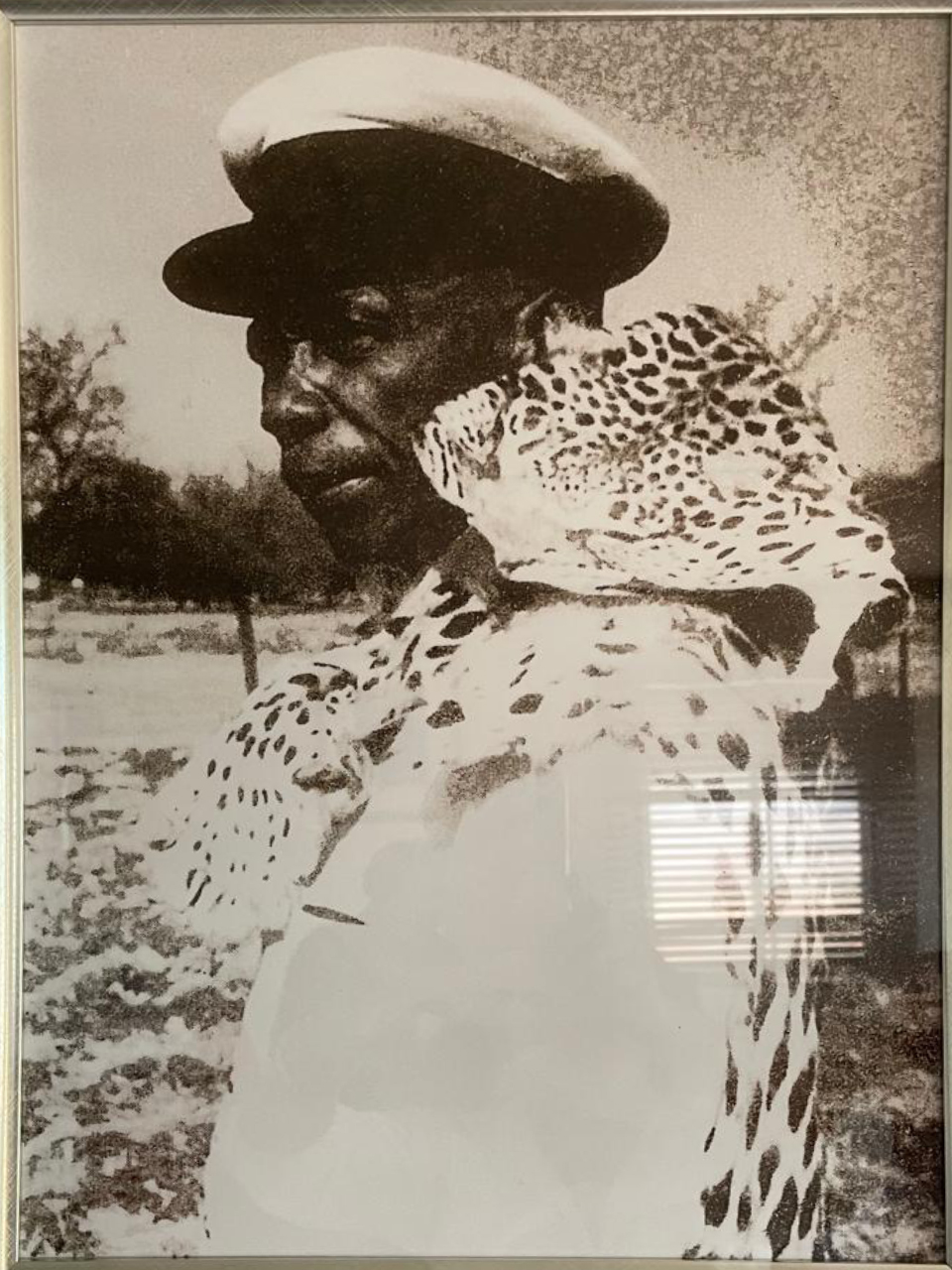

Kgosi Lucas Tshose Monnakgotla

(1974 - 1976)

Kgosigadi Tsheole Catherine (Mmadifeisi) Mma Morena Monnakgotla

(1966 - 1974)

FORCED REMOVALS IN THE PEOPLE’S MEMORY: THE BAKUBUNG OF LEDIG

Every human life, however humble it has been, has a context meshed of familiar experience –

social relationship, patterns of activity in relation to environment. Call it ‘home’, if you like.

To be transported out of this on a government truck one morning and put down in an uninhabited place is to be asked to build not only your shelter but your whole life over again, from scratch.

-Nadine Gordimer in The Discarded People, by C. Desmond, p xvii.

AT MOLOTE

In About 1837, or even earleri, the Bakubung settled at Molote in the Venterdorp district, Western Transvaal. While they were attacked by Mzilikazi. After the Boers had driven the amaNdebele beyond the Limpopo River, the clan then had to provide unpaid labour for the Boers who did not treat them well and they left the area, with the exception of a few, who ultimately retired to Motlhantle. They then wandered about in the Orange Free State eventually returning to their old home in about 1884, where they found that the Boers, some say General Piet Cronje, had taken possession of that piece of land.

The clan under their Chief, Ratheo (born between 1790 and 1805) who was then still living at Mmamonowe (district Heilbron, Orange Free State) collected money and bought two farms, Elandsfontein No. 19 and Palmeitkuil No. 17 jointly known as Molote in the Ventersdorp district from Rakometsi (a Boer identified as Albert Bosman by Meshack Monnakgotla). On the advice of Rev. Cludi of the Anglican Church who helped with transactions Ratheo’s signature on the title deed meant that in fact he was the private and sole owner of the land acquired.

In August, 1885 Lesele hived off with a large body of the parent clan and settled at Drarsfontein (Telengwa), which they eventually left in 1912 when they settled at Sekama (alias Mathopestad) adjoining Molote to the west as an independent Chiefdom of the Bakubung of Mathopestad.

Praise-Poem

Kubu kubu ntsha marota re bone,

Marota a kana ka ntlo ya moseme,

Ke batho ba seabudi sa metsi,

Kubu le kwena di dula mmogo metsing,

Tse ‘potlana di a sega di kakaletse,

Tse ‘kgolo dia sega ka letlhakore.

Translation:

Hippo hippo bare your shoulders let’s see,

Your shoulders are as large as a house built of reeds,

They are the people of the monster that lives in the water,

The hippo and the crocodile live together in the water,

The little ones glide upside-down (but) the big ones use their sides.

Bakubung descended from the Ghoya.

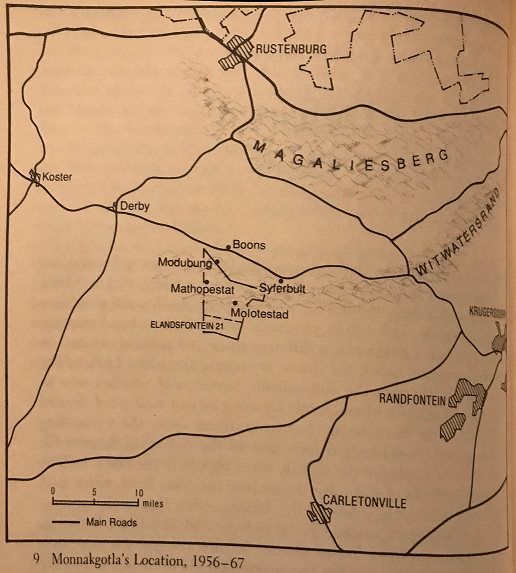

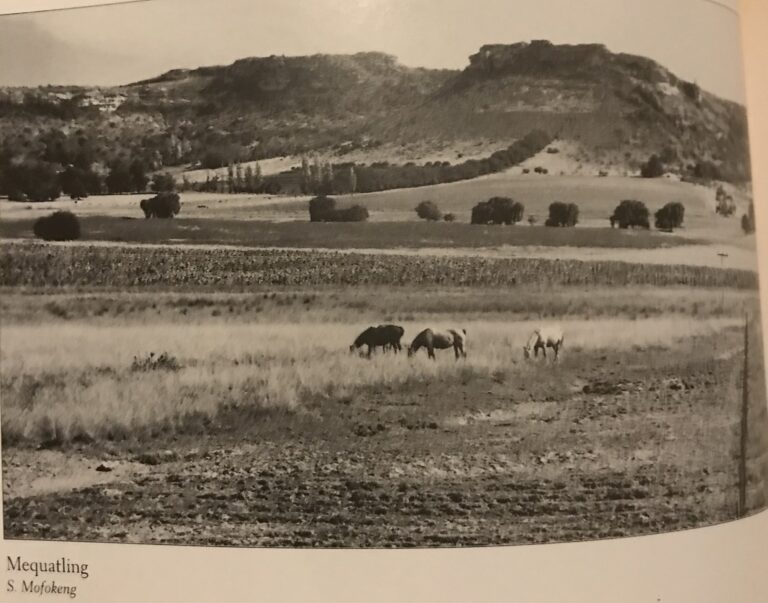

MOLOTE, BEFORE REMOVAL

This settlement was situated in a very fertile High Veld region, Southwest of the Magaliesberge. Three streams, the Mokgadi, the Madiba-matsho, and the Metsi-botlhoko which never ran dry throughout the year, flowed through this region. This means that Molote was well-watered region with abundant grazing facilities and excellent prospects for agricultural activities. The people lived off the land, i.e practicing pastoral and crop farming, with sorghum and maize as their mainstay. Wheat was also extensively grown and many people had orchards of deciduous fruit trees around their homesteads. Another sector of the population was engaged in wage employment on Boer farms in the neighbourhood of the settlement and in “white” villages such as Boons, eight miles away, and Ventersdorp which lies thirty-four miles from Molote, or further afield in Potchefstroom, Randfontein, Krugersdorp and Johannesburg.

AMENITIES:

There were two primary schools that catered for the pupils of this town, but no secondary school was in existence until the time of their removal. The people were largely Christains, most of them belonged to the Anglican (first Christian mission amongst the Bakubung) and Hermannsburg Lutheran churches. Although there was no clinic, a doctor came once weekly, on Thursdays, to attend to the sick.

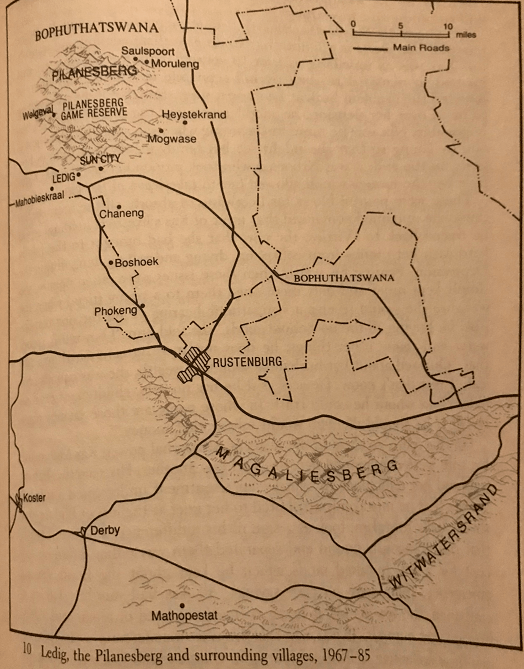

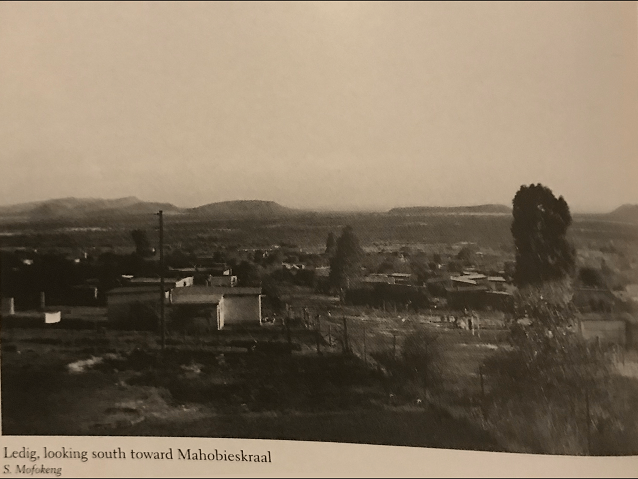

THE MOVE TO LEDIG

It was in the mid-1950s when it was first rumored that Molote was under threat of removal to Ledig near Saulspoort in the Rustenburg district because it was a “Black spot”. This was during the reign of Chief Lucas Tshose Monnakgotla who acted as regent for his deceased brothers’s son, Solomon, who was still a minor. The clan joined their chief in resisting the removal until the chief was detained and demoted. The state then looked for a collaborator and they found none other than the late Chief’s wife, Catherine, who was then installed chieftainess and she agreed to move. It must be borne in mind that to enable the state to carry out such insidious acts it had passed a welter of laws to give itself legal grounds to justify such actions over the lives of millions of voteless humans. For example, according to the Native Administration Act, 1927 (Act No. 38 of 1927), as amended, the Governor General (today State President) may appoint any person as chief of a tribe, may depose any chief or headman. Once the state has the co-operation of their nominee, no matter how vehemently the people protest that the government’s collaborator is not their chosen leader, as was indeed the case here, the state negotiations only with that “leader”. It claims that the whole clan is represented by him/her and through him/her they have agreed to move voluntarily. Once the chieftainess had “legalised” the removal the people of Molote were regarded as squatters on the land they had occupied for 129 years. The school was demolished and G.G. Government trucks moved in and conveyed the people to Ledig (New Molote), where they were dumped like garbage on the open veld.

By August 1966, about 600 families, consisting mainly of immigrants, had left, with 199 (of whom 183 were men) refusing to move. One respondent declared that the 199 families who refused to leave in August 1966 consisted mainly of the descendants of the original purchasers of the land. These supported the chief to the hilt. Some were tortured with the chief by the South African gestapo, convicted and served prison sentences with him. This group was the last to arrive at Ledig in 1969. The state had made an example of them so that other resisters would take their lesson from this punishment. To compound their miseries, the state ordered that all cattle had to be sold and an auction was actually arranged for 28 January 1969. The people that were not the offspring of the men who bought Molote, were the people who were endorsed out of the cities or came from white-owned farms and settled amongst economy and competitors. Otherwise, if they were no longer required, they became “surplus Natives”, liable for removal.

The modernization of the economy is another factor which led to African removals, especially from white-owned farms as mechanization decreased the demand for labour, rendered these people redundant, and made them victims of the labour tenant system. In short, this system made provision for the rendering of services for a certain period in the year (usually three months) to the white farmer by the African in return for right to reside in his farm, to cultivate a piece of land, to graze his (the tenant) stock. Such services to the white land owner have also been referred to pejoratively as “boroko” (literally sheep) by the victims of this system, namely, the Africans. Already in 1917, a labour tenant had complained that “a native is not allowed to hires a white’s farm by money, except by working for nothing but ‘Boroko’. As a result of the abolition of the labour tenancy system (1970) the farmers were forced to use mechanized farming methods. Sophisticated machines were imported which reduced labour requirements. The result was that many people became redundant on the white man’s farms. They could not go to the cities because of the pass laws, so they became targets for relocation. The surplus Africans were pushed of the white farms to the Bantustans. In this way the burden of responsibility and maintenance and welfare was shifted from the farmer to the Bantustan government under the guise of consolidation.

© 2025 Bakubung Ba Ratheo. All rights reserved | Legal Notices